(Photo credit: Paboco)

Paper Bottle

The Paper Bottle à la Paboco and Coca-Cola - A Prototype in Progress

Market requirements drive technology.

This also applies to packaging and especially to bottle developments. Sustainability is paramount today.

At the beginning of the PET era, that wasn’t an issue; sustainability was not yet a quality criterion for the PET bottle.

Today, the first and foremost focus is sustainability when analyzing new developments. And today, in many cases, sustainability is the driving force behind new projects.

The paper bottle is one such project. At the same time, it is an example of the delight in experimentation in the packaging industry. I mean that in the best sense of the word: thinking outside the box, with the aim of gaining experience, exploring alternative options, perhaps finding new solutions along the way. In any case, new insights emerge for optimizing products, packaging and sustainability. In this way, a new reality may emerge from visions.

One of the paper bottle experimenters is The Coca-Cola Company. The paper bottle is part of a series of projects that all pursue testing alternatives to the established and gaining knowledge. Another project of this series is “Enhanced Recycling,” which we reported in issue ONE:21.

I had the opportunity to speak to Stijn Franssen, Packaging Innovator at CocaCola and Tim Silbermann, Project Manager Product Development at Paboco. We wanted to talk about the technical aspects of the paper bottle. I know that especially those readers involved in the value chain’s technologydriven parts are curious to find out more details.

I’m also eager to understand how the paper bottle works. I would like to know how it compares with the PET bottle and other packaging variants so that I can get an idea of the potential behind such a prototype regarding a sustainable packaging solution. It is not my intention to evaluate the approach or the project as a whole. For me, it’s more about the engineering spirit that is necessary for such projects, that inspires teams and comes up all by itself in an exciting environment.

Right at the beginning, I have to dampen any hopes that you will find extensive technical information in this article. Coca-Cola and Paboco are still too covered when it comes to communicating technical details. During the conversation, my partners kept talking about “official communication” and used generally agreed wordings. Nevertheless, the meeting did not disappoint. It is the approach, the motivation, the commitment that fascinates me. And last but not least, the team spirit that is behind the paper bottle project and that drives it.

When we started our conversation, Stijn Franssen made it clear that the paper bottle at Coca-Cola is not a project like any other. If projects are usually determined by getting into something that one believes can be commercialized and whose development path is quite advanced, then none of that applies to the paper bottle.

Stijn attaches great importance to emphasize that this is a pilot project being part of the Coca-Cola sustainability program World Without Waste. On the one hand, it would be about avoidance, collection and recycling. But it would also be about stretching out feelers and tracking down innovations and alternatives. What do these developments promise? Curiosity and motivation speak from his sentences. Stijn and his colleagues have no intention of abolishing the PET bottle or can. No, the whole point of the paper bottle project is to try out alternatives and see what works and what doesn’t. “We know the advantages of PET; we know the advantages of glass and the can. And we are curious to find out the advantages of the paper bottle.”

“We are very much in the very beginning of a new type of technology. It’s a journey, and it will still take several years before we have a commercial, viable, scalable industrial product.” - Stijn Franssen

Could one of the advantages be shelf life? Stijn doubts that it makes sense to apply the same quality criteria today as in the 70s, 80s and 90s, when a shelf life of 12 months was an important quality criterion. He cites beverage production for a summer festival as an example. Sure: the drinks are consumed in no time. For such applications, and one can easily imagine other situations, he wants to have the perfect and most sustainable solution in his portfolio, solutions whose sustainability traffic light is green.

Paboco - the paper bottle company

Starting a few years ago, ecoXpac, a small Danish family-owned startup, decided to pave the way for sustainable packaging and develop probably what was the most challenging but also most impactful in the packaging sector for liquids – a paper bottle. Early on, Carlsberg found ecoXpac and became a key co-driver of the paper bottle development. Due to the open innovation approach meant to attract more partners, BillerudKorsnäs, a Swedish paper manufacturer, and later ALPLA, an Austrian bottle manufacturer, joined forces to carry on the development, which evolved into Paboco – the paper bottle company. Since then Paboco has onboarded more pioneer brands representing different product categories to drive the innovative spirit of the project and move faster ahead to bring the paper bottle to the market and consumers’ hands.

In the course of the conversation, I remember the early days of stretch blow molding technology and PET, when the first steps were to produce a preform from extruded pipe sections, then forming the preform base with a suitable tool and then blowing them. Then the next step: the base cup bottoms of the bottle. At that time, of course, no one thought about replacing glass or cans. Instead, it was about development, about seeing what works and what doesn’t. The example shows that engineers shouldn’t let the limits of their imagination hold them back. In the early days of PET, no one could have imagined an output of 2,700-2,800 bottles per hour and blow station, as is the reality today. Even not even ten years ago, this output was thought to be impossible.

“One of the key attributes of our packaging is that we can add beautiful and sharp design features, e.g. debossing or embossing, because paper is wonderfully formable.” - Tim Silbermann

The start-up Paboco, the idea behind the paper bottle, is also at the beginning of a development process and already took the first steps. Tim Silbermann reports that the Paboco team today consists of 36 people. Now it’s about upscaling, initially from pilot technology to production. In November 2020, Paboco installed its first production line with multiple cavities. This was the only way they could learn how the production conditions affect the paper bottle: What applies to 2,000 bottles, what applies to 10,000? What does it do with the process, with the quality of the paper bottle? “We have won partners with Carlsberg, Coca-Cola, L’Oréal and the Absolut Company. Partnering with leading manufacturers and actually working on the real products gave us learnings that we could only generate in such an environment.”

Tim reveals that the paper bottle prototype consists of one piece, there is no gluing of shells. A very thin liner made of rPET, representing the barrier, is hidden under the paper outer skin. On this basis, Generation One, production and learning began: “about filling lines, logistics, consumer experience, recyclability etc.” It is precisely on this basis that development is advanced. The paper bottles run on glass lines, on PET lines. That depends on the requirements of the partners - he calls them “pioneers”.

“In the end, we have amazing physical properties that help us in getting the bottle over the lines, and the learnings feed directly into the next development cycle. So, we use the requirements of an existing packaging as a starting point and develop the paper bottle to match the product, target market and packaging requirements. The combination of our technology for fiber processing and bottle design enables us to do this. This is all the more important for carbonized products. What we see is an excellent performance, which also leaves us room for further development.”

Paboco runs tests in its own laboratories. In addition, the team benefits of a great advantage that is also a catalyst: the partners also test, in their own laboratories and with their own products. Moreover, they give feedback to Paboco so that Paboco not only has a much more extensive database available than they would if they were developing entirely on their own; Paboco also benefits from an unbelievably large amount of external experience.

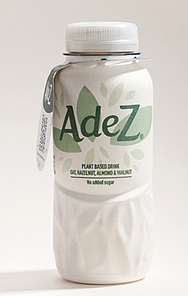

Coca-Cola is now taking the next step by making a test run with 2.000 bottles in Hungary. Given the usual outcome of Coca-Cola beverages, the volume is, of course, negligible. Nevertheless, the project is supposed to deliver data from several levels and is therefore particularly interesting: Coca-Cola works with an eCommerce partner: How does the handling work? What are the challenges to be overcome? In addition, the end customers are asked to give feedback. Even the bottled beverage itself, AdeZ, as a pH-neutral, plant-based product, is not a standard for filling and brings with it challenges. Coca-Cola and Paboco will evaluate the results together; the next development circle can follow before the teams plan another market test run.

We are talking about the structure of the paper bottle, and Tim describes the principle of Generation One. The paper bottle process comprises three steps: 2 times paper + barrier layer. This process is fixed and does not change for further developments.

I had to throw my idea overboard, namely that a PET bottle, whatever the wall thickness, would be blown and then wrapped in paper. In fact, the process is reversed: First, the pure paper bottle is created, then it is provided with a barrier. The paper fibers are processed purely mechanically, without the addition of additives or chemicals. Tim: “We refine the paper fibers on-site in a very special recipe. It’s just mechanical refining of the pulp. It has to be grinded and cut and opened.” In Generation One, the barrier is a liner made of rPET, made from a “very, very thin and minimized weight rPET preform – far less than used for a traditional stand-alone plastic bottle“.

Stijn and Tim do not describe the process itself in detail. Just this much: After the treatment of the paper fibers, the paper bottle blank is created, which is then dried. In this phase, the paper bottle gets its strength properties, based on the compression of the paper fibers, and also its final shape. So, everything is done by temperature and pressure.

Both injection moulding/preform manufacturing and the blow moulding process use modified standard technology to produce the rPET liner. Stijn: “The paper bottle with its rigid paper shells enters the modified SBM machine and comes out again at the other end with an rPET bottle inside.” Stijn does not hide the fact that introducing the barrier, i.e., blowing the preform inside the bottle, is a challenge.

Generation One is the prototype that allows the paper bottle to be produced. The rPET liner inside, blown from the rPET preform, provides the barrier, and the neck finish of the preform allows the use of existing closure systems.

According to Stijn, these two points are precisely the challenges for further development work: waiving the barrier layer made of plastic and realizing a neck made of pure paper. Stijn often hears that the paper bottle is not yet a solution: “Yes, that’s right, we only have a solution when we have solved the two major tasks. But we do have a part of the puzzle already, which is a thin-walled, rigid paper shell. We can work with it, test the paper bottle and see how it behaves on the filling lines. The paper bottle is still in the prototype phase.”

I was able to elicit a few more details: The wall thickness of the 350 ml Paboco paper bottle prototype is around 1 mm. The total weight is made up of 15g paper and 8g PET. Stijn describes the stability: “Since it is so light, I expected something like an eggshell. But when you hold it in your hand, it is really as strong as a can or a PET bottle.” Top load and burst pressure would be in the range of the corresponding values for PET bottles. The “superior strength” would come from paper, because the measured values are in high ranges even without PET inside the bottle.

Tim is enthusiastic about the paper bottle’s design freedom: “One of the key attributes of our packaging is that we can add beautiful and sharp design features, e.g. debossing or embossing, because paper is wonderfully formable.” However, this also has disadvantages: During the process similar to classic SBM with similar tooling, a fairly sharp splitline occurs.

I want to know whether oval bottles are also conceivable or large-volume or particularly small bottles. Large-volume containers are already being produced as prototypes, and Tim is convinced that oval bottles and small bottles are also possible and have already been taken into account for future development steps.

We learned that the first Coca-Cola paper bottle is a prototype made of paper plus rPET barrier plus standard plastic cap. The further development aims primarily to dispense with plastic as a barrier and make the neck out of paper. I am thinking about the challenges with necks made of paper: Is it the production/design itself or the stability of the thread? Since the fiber shape is good, explains Tim, the challenge is to understand the stability and strength of a paper neck: It is essential to determine what the abrasion causes when closing a paper neck with a thread and whether the sealing works the same with such a new material.

And what will the closure look like in the future? Plastic? Paper? Paboco’s final solution is the full paper bottle - this also includes a closure made of fibers. Tim says his team is already working on it.

As far as I understand it, the paper bottle should be disposable with waste paper. So the paper could be kept in circulation. Can a paper bottle come back as a paper bottle? Is that technically possible and what are the legal requirements, nationally and internationally? Tim: “We can make paper bottles out of recycled fibers. However, paper has no different grades during recycling. That means it is currently not really traceable where the recycled paper mixture comes from originally, so the risk for contamination is higher and therefore regulations are tight. If the bottles would be collected in separated streams this could however be legal.”

The comPETence center provides your organisation with a dynamic, cost effective way to promote your products and services.

magazine

Find our premium articles, interviews, reports and more

in 3 issues in 2026.