Why an article about intercultural competence in this technical magazine?

The answer is that in spite of what many people think, culture isn’t soft and fluffy but can be made really tangible. It is quite possible to measure it and therefore it can be understood and managed.

In an age where the entire industry is chasing those next few tenths of a gram of PET weight reduction, those next few bits of energy savings, that next step in logistics savings, understanding and managing culture can significantly contribute to your organizational effectiveness and therefore to your bottom line.

The following quotes from a report published by “The Economist Intelligence Unit in 2012” illustrate the situation very well [1].

“Effective cross-border communication and collaboration are becoming critical to the financial success of companies with international aspirations.”

“Misunderstandings rooted in cultural differences present the greatest obstacle to productive cross-border collaboration.”

“Most companies understand the cost of not improving the cross-border communication skills of their employees, yet many are not doing enough to address the challenge.”

The challenge

I am pretty sure that at some point in time and very likely more than once, you have let out a deep sigh of frustration because the behaviour of whoever you were working with seemed utterly abnormal, illogical, incomprehensible and maybe even downright weird.

For those of you who work with people from other nations, this probably is a common occurrence. International relationships, be it in B2B commercial negotiation, project management, after sales service, international project groups, etc. always have an additional layer of complexity and present extra challenges.

It is already not so easy to work harmoniously with people that grew up together and hence have the same frame of reference or the same ‘normal’. It is clearly much harder if you add an additional layer and have to find a way to work effectively with people that come from different countries and probably have very different ‘normals’. It is really hard not to think in terms of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. After all, we feel that the way we do things is ‘normal’ and therefore ‘right’.

The logical consequence of that is that the other must be ‘abnormal’ and therefore ‘wrong’. We are all human and have this same innate reaction. It is easy to see that this behaviour can be at the core of many challenges we face.

I’d like to introduce you to a system, developed by an engineer who later became a Professor in Sociology because he was interested in the human side of organisations. Prof Emeritus Geert Hofstede is very well known in the academic world as the father of comparative research in national as well as organizational culture. Although national and organizational cultures interact, the two are distinctly different but are often mixed up. Before we can dive into the subject, we first need to define what we mean by culture.

Prof. Hofstede defines culture as ‘The collective programming of the mind by which one group distinguishes itself from another’ [2] .

In his definition, culture can be represented as different layers of an onion (see figure 1) and national culture is at the level of our deepest, mostly unconscious values. We have learned those from our parents and our larger environment in the first 10 – 12 years of our life and they define our ‘normal’. You can look at it as the way we were programmed in our younger years. It is part of our core programming, part of our operating system which is always there without us actually being aware of it just like the biggest and most important part of an iceberg is under water and invisible.

Organisational culture is situated in the outer 3 layers. It’s much more about how we agree to do things in an organisation, our practices, our rituals and our symbols. You can look at it as the layer of programming we actually feel, see and work with just like the Windows Office programs you use every day.

This article relates to national culture only. It is about the unwritten rules of the game in each society. Although we are aware of the rules in our own society often we are unable to accurately describe them. The question we face is how to discover and understand the unwritten rules of other societies.

D1: Power Distance Index (PDI)

This dimension expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. The fundamental issue here is how a society handles inequalities among people. People in societies exhibiting a large degree of Power Distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. In societies with low Power Distance, people strive to equalise the distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities of power.

D2: Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV)

The high side of this dimension, called individualism, can be defined as a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of only themselves and their immediate families. Its opposite, collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society‘s position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we.”

D3: Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS)

The Masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material rewards for success. Society at large is more competitive. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensusoriented. In the business context Masculinity versus Femininity is sometimes also related to as „tough versus tender“ cultures.

D4: Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

The Uncertainty Avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? Countries exhibiting strong UAI maintain rigid codes of belief and behaviour and are intolerant of unorthodox behaviour and ideas. Weak UAI societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles.

D5: Long Term Orientation vs. Short Term,

Normative Orientation (LTO)

Societies who score low on this dimension, prefer to maintain time-honoured traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion. Those with a culture which scores high, on the other hand, take a more pragmatic approach: they encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.

D6: Indulgence vs. Restraint (IND)

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms.

6D Model

Prof Hofstede’s 6D model is a tool that provides a common language and turns culture from something fluffy into something tangible, measurable and manageable.

He used countries as a proxy for ‘groups’ because often (but not always) people within one country have a similar history and have developed a common culture. If you think of a country, France, Germany, USA, etc., I am pretty sure you have a picture in your mind about the stereotypical Frenchman, German or American.

The 6D model expresses this ‘typical’ person in 6 numbers on 6 so-called ‘dimensions of culture’. Please read the inset for the descriptions of the dimensions of culture. Each dimension has a scale from 0 to 100. It is critical to understand that neither 0 or 100 or any score in between means ‘good’ or ‘bad’. It is just a way to create a language, which helps to express relative positions and creates the basis for understanding.

Example

Let’s look at an example. Throughout the world, the Dutch are generally considered to be unusually direct in their style of communication. Quite a few societies perceive this directness as offensive and sometimes even arrogant. However, amongst themselves, they don’t see it like that at all. For them, speaking up and saying what they think, regardless of who is in the room is normal and everyone is expected to do so, as it is considered the optimal route to the best end result.

Let’s compare this with Belgium. Despite it being a country with different language groups, culturally it is actually quite homogenous when you look at it from a global perspective. Despite the fact that 60% of Belgians speak the same language as the Dutch, from the perspective of national culture, they are quite different. This may seem strange but ask any Belgian or Dutch person and they will confirm it.

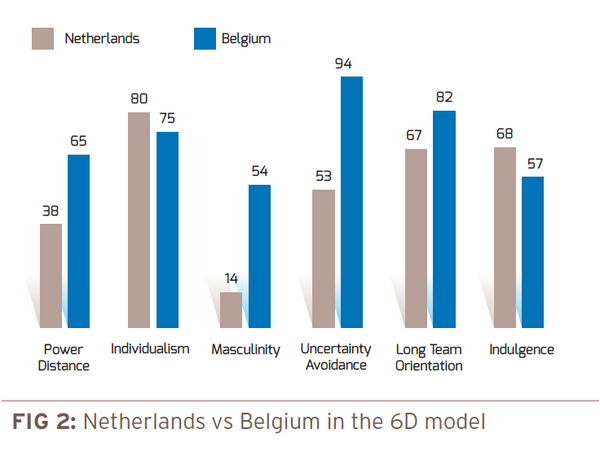

This difference can be described by 2 of the 6 dimensions (PDI & MAS) of Prof Hofstede’s model. The graph in figure 2 illustrates the differences between the 2 countries.

As you can see, the differences in scores on some dimensions are quite pronounced. There is a 27-point gap in Power Distance (PDI), which means that on average, hierarchy is significantly more important in Belgium than in the Netherlands. Looking at it in different way, it means that the Dutch society is significantly more egalitarian than the Belgian society.

Translating the Dutch ‘directness’ in terms of PDI, a Dutchmen is much more likely to speak up in a meeting regardless of whether his boss or his boss’s boss is in the room. The average Belgian will become quieter the more ‘higher-level’ people are in the same room out of respect or maybe even fear for hierarchy.

The Netherlands score 40 points lower on the Masculinity (MAS) dimension which in a business context means they are very consensus-seeking. Belgium is significantly more masculine which means it tends more towards a competitive style of behaviour where it is more important to win than to find consensus. This helps to understand the Dutch behaviour because in order to achieve consensus, it is necessary and very much expected that each participant speaks up so that everyone’s input can be taken into account to achieve this consensus.

A word of caution; consensus is not to be mistaken for compromise. A compromise means each party concedes a bit and middle ground is somehow found. All parties tend to feel that they had to give something up and are only partly satisfied. In the case of consensus, very often, a new and more creative or innovative solution is found which suits the needs of ALL parties. Now each party tends to be happy with the result and will support the outcome. Understanding the difference between compromise and consensus and understanding which country works in which way is crucial in any international setting.

In this particular example, if each party understands the other’s cultural framework e.g. the Belgian understands that the Dutch guy is genuinely trying to work towards a consensus and the Dutch guy understands that in Belgium, hierarchy, status and winning are important, then with a little bit of goodwill, they can find a way to respect each-others ‘normal’ and establish sufficient common ground to work together productively.

Example

Let’s take a different example and look at teamwork. In a high PDI country, it is very important to have a clear team leader who has the power to make decisions. He will be expected to do so by his team members who will quite naturally defer to him. Suppose you appoint someone from a low PDI egalitarian country as team leader, he will try his hardest to be ‘just one of the group’ as would be normal in his own environment. If he is running a team in a high PDI country, this will not work at all because his team members will expect him to assert himself. They will very naturally want to defer to him and expect him to make the decisions. It makes them very uncomfortable and they will not respect him if he tries to be ‘one of them’.

The opposite situation is just as challenging. A leader from a high PDI country will find it really hard to work in a low PDI country because he’s used to respect for hierarchy and for his status, which is an alien concept in a low PDI country.

Also in this example, awareness and understanding of the simple realities of the different cultural frameworks provide the information needed to be able to successfully adapt one’s natural way of working to this new environment.

You will have started to realize that common intercultural management issues can easily be described in the language of the 6D model. Once you do that, it becomes a lot easier to understand what is actually going on and positive action can be taken to manage the situation.

So far, we have explored 2 out of the 6 dimensions and you may begin to think that the possible combinations are too many to be able to manage effectively. Fortunately, it is possible to group countries in clusters, which have similar characteristics. By doing this, one loses a bit of detail but for many aspects of business it is ‘good enough’ and one can always dive deeper into the details should the need arise.

Culture cluster

One of my colleagues at Itim International, Huib Wursten, developed the 6 culture clusters and gave them each a ‘mental image’ which helps to visualize their main characteristics. Each of the clusters are distinctly different but most people within them exhibit similar behaviours and have similar expectations on business matters such as leadership, teamwork, reward systems, B2B negotiation, etc. Each country in the world can be classified in one of these culture clusters [3].

1. The Contest Cluster

2. The Network Cluster

3. The Well-oiled Machine Cluster

4. The Solar system

5. The Pyramid Cluster

6. The Family Cluster

One example, which illustrates the concept well is the MACHINE cluster. It encompasses countries such as Germany, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic and German-speaking Switzerland. I am sure you recognize the common characteristics of these countries. These countries are all very process-driven and intrinsically have a high respect for professional expertise. Using the language of the 6D model, they all score low on Power Distance (PDI), high on Individualism (IDV), high on Masculinity (MAS) and high on Uncertainty avoidance (UAI).

In this cluster, you will very likely be successful using the same organizational models, the same leadership style, the same commercial approach, etc.

Hang on you may think, Germany seems quite hierarchical to me with all their titles … so how come they score low on PDI?

This is a reflection of high Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) rather than PDI. Germans aim to build well-functioning systems and trust experts to manage the process of doing so. The titles are an expression of this expertise, which earns recognition and trust.

Many cultural trainings only offer answers to questions which address the surface layers of rituals and symbols. Clearly it is important to be aware of these as they will help you avoid situations which your counterpart may find offensive or make you look ignorant.

However, by now you will have understood that our approach to intercultural competence is at another level altogether. It has a strong scientific foundation and addresses the question ‘WHY?’ rather than the questions ‘HOW?’ & ‘WHAT?’

Understanding the 6D model helps you understand the mind-set of the people you are working with. The scores of a country on the 6 dimensions give you a lot of information about that country’s ‘normal’. When you compare them to your own normal you will be able to see the main differences and have a good idea of what it actually means for you in your day-to-day interactions. This goes far beyond the rituals and symbols and is invaluable in any situation where you need to work across borders or even within borders in diverse teams with members of different cultural backgrounds. It not only avoids problems but much more importantly it transforms the possible size of the ‘common ground’ of a diverse team from the lowest common denominator where everyone (hopefully) is trying to be polite and respectful to a situation where each participant understands the other’s ‘normal’ and a substantially larger ‘common ground’ develops. Once arrived at this situation, team members will feel better understood and feel safer. As a result, they will be more engaged and contribute more freely and proactively to the success of the team. This drives creativity and innovation and leads to substantially enhanced performance of the organization.

The ultimate point however is the Jerry Maguire one: ‘SHOW ME THE MONEY!’ (If you haven’t seen the movie, I recommend you watch the extract on YouTube)

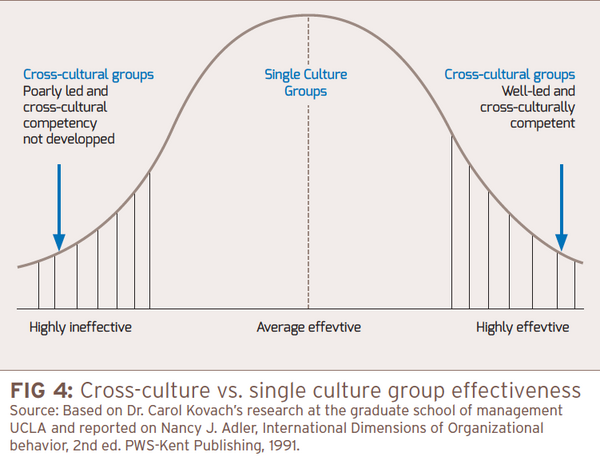

There are many studies about the impact and challenges of diversity on the performance of a corporation. Meta-studies (a study of the results of many individual studies) have shown that well-managed diversity shows a strong positive correlation to excellent financial performance of a company. On the other end of the scale, poorly managed diversity correlates to poor financial performance (see figure 4). With poorly managed we mean either a sledgehammer approach where the values of one national culture are imposed on others or an ostrich approach where the importance of the topic is wilfully denied like an ostrich who puts his head in the sand in the face of danger.

The term ROI is well known as “Return on Investment” but also stands for “Risk of Ignorance”. You just need to look at a few well known spectacular failures such as Walmart’s failed attempt to enter the German market which was due to a lack of understanding of the German culture or Korean Air’s terrible safety record from 1970 onwards until finally in 1999 it was recognized that a cultural issue was the true root cause of most of the plane crashes.

If you are in a business with huge margins, you may be able to afford to discard the impact of culture but if you are looking for that next area of P&L improvement, actively managing the aspects of culture in your business can be a good place to start.

itim International is a worldwide network of highly specialized consultants available to help you develop your intercultural competency and skills. We will guide you to a level of conscious competence and provide you with a set of tools that will allow you to better understand the mind-set of most societies in the world.

Outlook

In the next article, I’ll explore the field of organizational culture and how it can be measured and managed to support the strategy of your business.

The comPETence center provides your organisation with a dynamic, cost effective way to promote your products and services.

magazine

Find our premium articles, interviews, reports and more

in 3 issues in 2026.